For development financial institutions (DFIs) and impact investors determined to honor the mantra of ‘leave no one behind’, investing in fragile states is no longer an option but an imperative. The question, therefore, shifts from if to how: how to effectively invest in fragile and conflict-affected settings?

During the course of our lifetime, we have been witness to the greatest reduction in poverty in history. This positive development has improved the lives of over 1 billion people. Impact investing - further spurred by the Sustainable Development goals (SDGs) with its focus on eradicating extreme poverty (SDG1) - has contributed positively to this achievement. However, over the past few years and for the first time in decades, hard-won development gains are experiencing a reversal.

All actors working in the field of international development are now well-aware of one often cited and sobering World Bank figure: by 2030, 80 per cent of the global poor will be living in fragile and conflict-affected settings (FCS). Indeed, armed conflict is one of the most active drivers of extreme poverty and, at this moment in time, the world has the highest number of violent conflicts since 1946. The war in the Ukraine has brought the realities of armed conflict into sharp focus, with far reaching and often devasting national and global impacts, particularly on least developed countries.

FCS are not only the toughest markets; they are also the most difficult places to live and to thrive. Access to basic services is often minimal or lacking, and these challenges are compounded by low levels of security and weak rule of law. These dynamics have immediate effects on lives and livelihoods, and they have lasting impacts on generations to come.

While the risks of investing in FCS have been traditionally perceived as ‘high’ or even ‘too high’, for development financial institutions (DFIs) and impact investors determined to honour the mantra of ‘leave no one behind’, investing in such contexts is no longer an option but an imperative. The question, therefore, shifts from if to how: how to effectively invest in FCS?

Many DFIs and impact investors have built up experience and portfolio’s in FSC. However, we believe that investors will need to make both conceptual and practical shifts in terms of how they approach and engage in FCS, if they are to meet the challenges and optimise the opportunities to have positive impact.

Investing in FCS must be underpinned by several critical conceptual considerations. First, a deep understanding of double materiality. In FCS, the risks posed by the context to the investor must be accounted for and managed in equal proportion to the risks that the investor and the investment poses to the context.

As underscored in the 2022 United Nations’ guidance on ‘Heightened Human Rights Due Diligence for Business in Conflict-Affected Contexts’, these risks are two-fold: risks posed to people, or human rights-related risks; and, risks posed to the conflict, or contextual-related risks. Put simply, there is a risk that investments in FCS inadvertently feed into the dynamics of conflict, which may harm people and feed into the dynamics of fragility and violence.

Second, an appreciation of the risks and opportunities. Since we know that investments that are insensitive to the context can exacerbate fragility and conflict, it stands to reason that it is also possible for investments – sufficiently tailored to the contextual dynamics - to contribute to the dynamics of resilience and peace.

The opportunities in FCS therefore are three-fold and should go hand in hand for transformative effects; there are opportunities to contribute to:

These conceptual shifts have important implications for the practical steps DFIs and impact investors should take when investing in FCS. We believe that investments must be guided by three practical considerations.

Knowledge refers to the need to understand and grapple meaningfully with the dynamics of conflict and fragility; it is underpinned by an understanding that investing in FCS is not ‘development as usual’ but requires carefully calibrated, contextualised and adaptive approaches. Investing in FCS means equally investing in FCS-related knowledge i.e., broad-based expertise on conflict analysis, political economy and conflict-sensitivity on the one hand, and – depending on country-specific strategy adopted - country- and/or sector-specific knowledge on the other.

Networks refers to the need to work with diverse international, regional, national and local actors; the emphasis on networks is based on the knowledge that no actor alone can effectively address the challenges of FCS. These challenges require concerted efforts based on meaningful partnerships and exchange. DFIs must work in a ‘networked manner’ with other DFIs, multi-lateral development banks, national governments, non-governmental organisations, academics and multi-lateral organisations, such as the United Nations. By working through and with a vast, inter-linked network of actors, it becomes possible to work on market creation and ensuring that there is a bankable pipeline of investments.

Capital has two-facets: financial and human. Financial capital in its purest form refers to the debt, equity, grants, bonds and blended finance instruments that investors have in their ‘toolbox’. The financial capital we deploy must be flexible and equally adapted to the realities of FCS; we must use these financial tools to undertake high impact, pioneering transactions. But these transactions will only be effective if they are matched by the human capital required to invest in FCS. This may require different profiles and skill sets, including significantly higher motivation to focus on impact, a large dose of patience and incentive structures to match.

2. Second, DFIs and impact investors must respect minimum standards when investing in FCS. These minimum standards are designed to manage the risks posed by the context to the investor in question in equal measure to the risks posed by the DFI to the context.

Minimum standards entail first and foremost ensuring clear strategic positioning, including internal alignment on key concepts such as: definition of success and return; performance; minimum standards for 'Do no harm'; and, conflict-sensitivity. There should then be internal clarity on what drives investments, the linkages with incentive structures, implications for monitoring and how the strategic position will be communicated effectively internally and externally. In FCS what matters more is depth of impact over investment volume.

Moreover, investors must adhere to the practice of conflict-sensitivity. Conflict-sensitivity entails ensuring that investments at a minimum ‘do no harm’ – a cornerstone of the international development agenda as codified in the OECD-DAC 2007 principles for good international engagement in fragile states – and identify opportunities to contribute to peace. Conflict-sensitivity involves: understanding the context; the current or potential interaction effects between the investment and the context; putting in a place strategies to minimize the negative and maximise the positive contributions to conflict and peace; and, effective monitoring.

Lastly, minimum standards entail more rigorous investment-specific due diligence in FCS than are typically undertaken in non-FCS contexts. It requires understanding how the investment contributes to strategic positioning; broadening the consulted stakeholders, including through ‘stress-testing’ with non-DFI partners; enhanced Know Your Customer (KYC); and, a deep-dive on the specifics of the investment to be able to explore where the investment risks doing harm, and where opportunities for peace and stability maximisation can be harnessed.

3. Third, investing in FCS then involves making one of four strategic choices - based on the risk appetite, resources and impact preferences of each DFI/impact investor in each context.

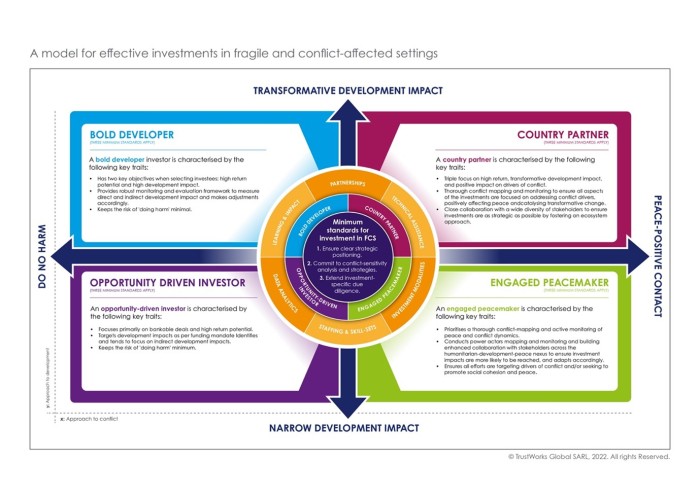

The decision of what type of impact to aim for in a given FCS can be considered through two key dimensions.

The first impact dimension concerns peace and conflict. Here the investor may decide that their prime goal is to avoid contributing directly to conflict, in which case the focus will be on ‘do no harm’; alternatively, the investor may seek to have direct positive impacts on the drivers of conflict and fragility, in which case the investor will seek to maximise peace-promoting impacts.

The second impact dimension concerns development. The investor may choose to focus on narrow development impacts, for example of a specific community or sub-region or to contribute to a specific Sustainable Development Goal (SDG); or, the investor may decide to aim for transformative development impacts, for example by seeking to transform an entire sector, or even impacts that manifest at the national level.

The intersection of the two dimensions leads to four possible FCS investment strategies or ‘options’ for investments in FCS, as highlighted in the diagram below: opportunity-driven investor; bold developer; engaged peacemaker; or country partner.

The selected ‘option’ then has implications for how investment modalities are deployed in order to achieve these objectives. We have identified six investment modalities that can be deployed and adapted to enhance the ability to meet these objectives: technical assistance; investment modalities; staffing & skill-sets; data analytics; learning and impact; and partnerships.

How each of these six investment modalities can be adapted to investor profile selected can be explored in greater detail in the interactive model developed by TrustWorks, here.

A way forward

DFIs and impact investors have played a crucial role in private sector development. To achieve the SDGs and, in particular, to eradicate extreme poverty, they have a crucial role to play in FCS.

DFIs and impact investors must acknowledge and act upon the responsibility they share to support the world’s most vulnerable populations. This requires embracing the complex realities of investing in FCS by engaging meaningfully with the political economy of fragile states and consistently incorporating heightened due diligence or conflict-sensitivity into both policy frameworks and practices on the ground.

This way of investing may well push some investors outside of their ‘comfort zones’. This underscores even further the need for new, meaningful partnerships. By combining the ‘KNC Triangle’ approach with the minimum standards and four strategic choices outlined above, it becomes possible for investors to work alongside other actors and to further their efforts in FCS in a manner that maximises impact and returns.

By making the conceptual and practical shifts outlined here we believe it is possible for DFIs and impact investors to increasingly work together in a manner that contributes in mutually reinforcing ways to both peace and development.

*To read more about this topic, please see the report commissioned by FMO and led by TrustWorks in partnership with NIRAS, entitled ‘The conditions for successful investments in fragile and conflict affected states (FCS)’ for the Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank (FMO), Switzerland, November 2021.

This article was written by Jeroen Harteveld and Josie Lianna Kaye.

Jeroen Harteveld (MsC) is the Fund Manager of MASSIF at the FMO; MASSIF actively invests in fragile states through local financial intermediates that provides access to finance to MSME’s. The fund is currently is active in over 40 countries with >125 investments and a portfolio of EUR 650 million. Jeroen contributed to this article in his personal capacity and the views reflected here do not necessarily reflect the view of FMO.

Josie Lianna Kaye (PhD) is the CEO & Founder of TrustWorks Global, a Swiss-based social enterprise with expertise in supporting companies and investors to operate in fragile and conflict-affected settings in a manner that is conflict-sensitive, collaborative and innovative. TrustWorks’ purpose is to prevent conflict, promote stability and foster peace-positive development with a view to improving the lives and livelihoods of the world’s most vulnerable populations.